Evaluating and Managing Deer-Damaged Cotton (Collins& Edmisten)

go.ncsu.edu/readext?520194

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

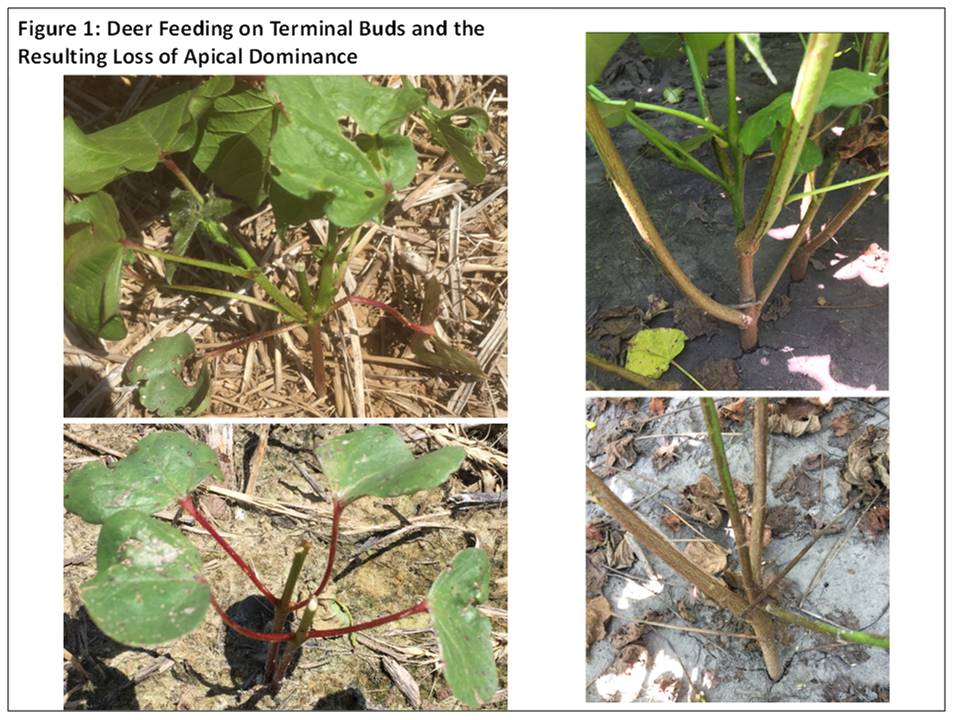

Collapse ▲In recent years, many growers have noticed an increasing incidence of deer feeding in young cotton. There are many theories as to why this may be occurring now, relative to years prior. The most common theories are the loss of aldicarb applied in-furrow for thrips and nematode control, major reductions in peanut acreage in the early to mid 2000’s, and the resulting absence of preferred food sources during that time. The number of deer feeding complaints in cotton has risen sharply in the last five years; however, these cases are relatively isolated to fields that regularly encounter noticeably high numbers of deer and fields in close proximity to preferred bedding habitat. Deer appear to feed on young cotton (less than five to eight true leaves) until other preferred food sources become available. Feeding preference is primarily on the terminal bud, thus causing a loss in apical dominance (Figure 1), which results in the majority of the harvestable bolls appearing on multiple vegetative branches. Preliminary observations suggest that deer feeding can cause severe stand loss, delayed maturity, and yield reductions in surviving plants. It is important to evaluate and quantify the effects of deer feeding on young cotton so that replant decisions can be made in cases of significant stand loss or severe yield loss of surviving plants.

Typical Symptoms of Deer Feeding:

Figure 1. illustrates the common effects that deer feeding has on surviving young cotton after some time has elapsed. The bottom left photo shows where the terminal bud has been removed by deer leaving only the cotyledons. As long as the cotyledons remain intact, they will provide an energy source to later trigger the development of new vegetative branches (top left photo) within a few weeks. These plants will most likely survive, however apical dominance has been lost (right photos), therefore growers can expect a severe delay in maturity of surviving plants, and in many cases, some degree of yield loss depending on when deer feeding occurred.

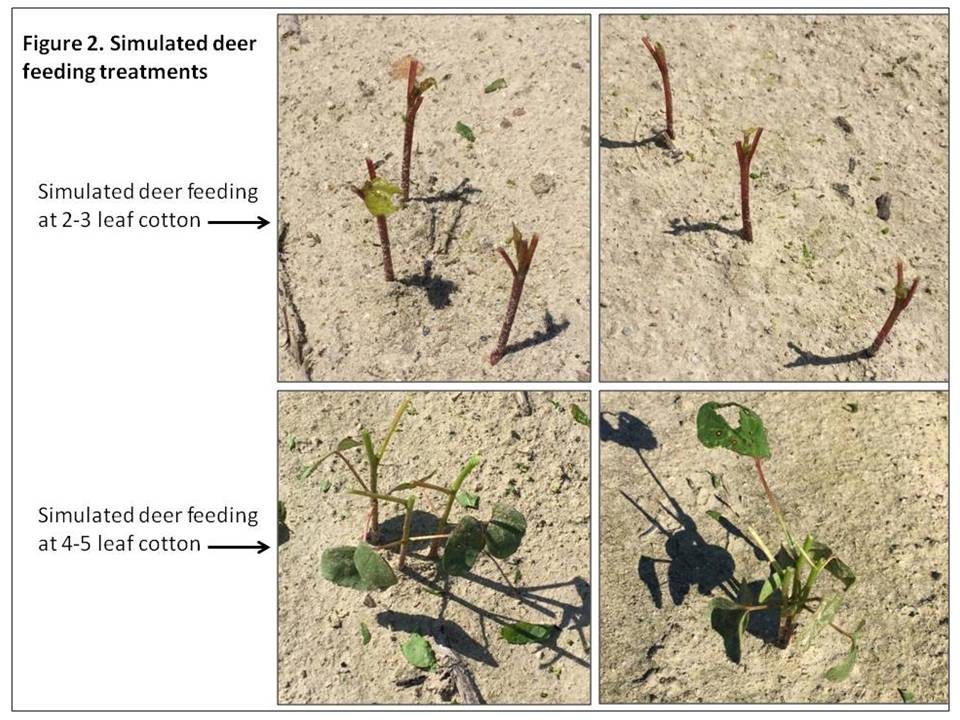

Figure 2 illustrates the effects of simulated deer feeding to cotton at both the 2-3 leaf stage and the 4-5 leaf stage. When feeding occurs at the 2-3 leaf stage (assuming deer didn’t feed below the cotyledons), the terminal bud has either been removed or is severely damaged. The cotyledon leaves have also been removed but the cotyledonary petioles remain intact, and will give rise to new vegetative branches at the junction of these petioles and the main stalk, assuming sunlight, soil moisture, and temperatures remain favorable. When feeding occurs at the 4-5 leaf stage, the terminal bud is completely removed but the entire cotyledons and some of the petioles for the first couple of true leaves remain intact, which will also give rise to new vegetative branches. Generally speaking, the more leaves that remain on plants that have been damaged by deer feeding, then the more likely and the sooner new vegetative branches will develop. However, when feeding occurs on larger plants, the crop maturity is delayed more so than when feeding occurs on younger plants, simply because there is less time remaining in the season for new vegetative branches to develop bolls that will contribute to yield.

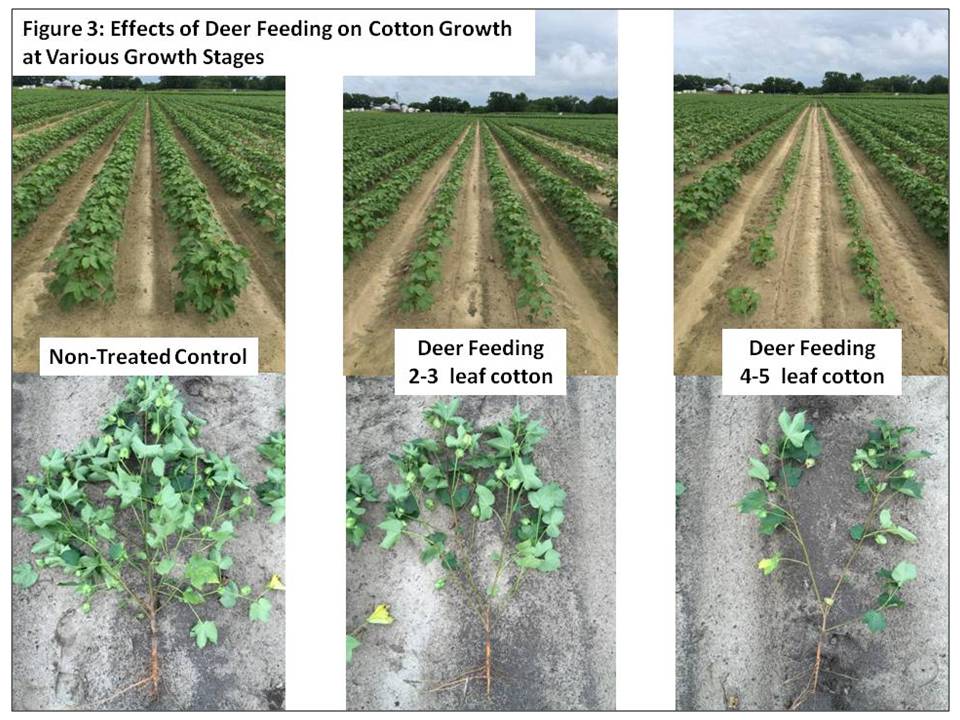

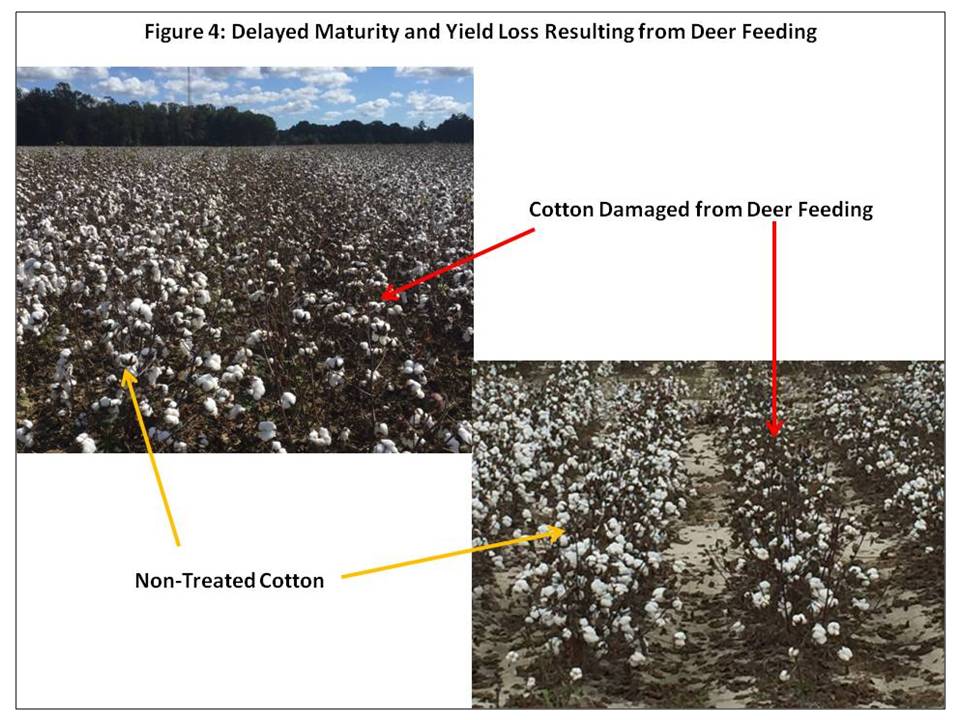

Figure 3 illustrates a side by side comparison of deer feeding damage at various growth stages. The top row of photos illustrate the delay in maturity caused by deer feeding within a few weeks after the damage occurred and new vegetative branches are beginning to develop. The bottom row of photos illustrates the severity of these delays in maturity through the loss of apical dominance and lack of yield-contributing bolls that are important for maintaining yields. Figure 4 illustrates the effect of deer feeding on maturity and yield at the end of the season once all bolls are opened. In many cases, surviving plants that were affected by deer feeding have a significantly lower number of bolls, or a few more late-maturing vegetative bolls are too delayed to contribute to harvestable yield.

Impacts of Deer Feeding on Yield:

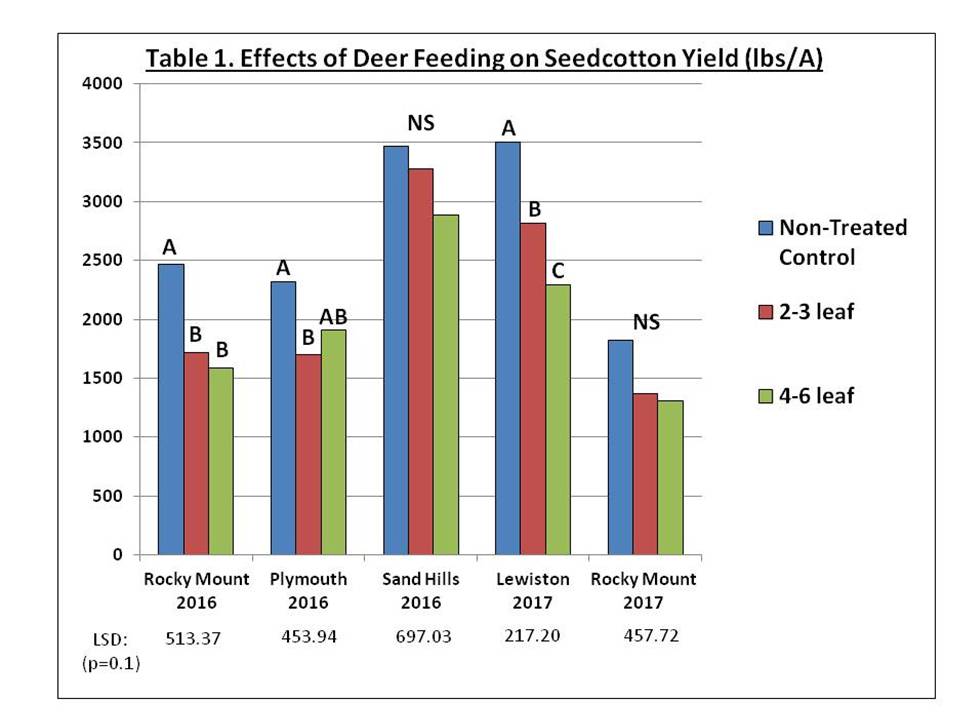

Research conducted during 2016 and 2017 across North Carolina suggests that simulated deer feeding consistently resulted in a loss of apical dominance, altered growth, and delayed maturity of cotton across all environments. Simulated deer feeding resulted in significant seedcotton yield reductions in three out of five environments in both years of the evaluation (Table 1). Reductions in seedcotton yield appeared to be the result of fewer bolls per plant, delayed maturity as most harvestable bolls appeared on vegetative branches, and a lack of suitable time or growing degree day accumulation for post-injury recovery to occur. Simulated deer feeding at the 4-5 leaf stage resulted in greater losses of seedcotton yield compared to feeding that occurred at the 2-3 leaf stage in four out of five environments. Reductions of seedcotton yields appeared to be greater when feeding occurred at the 4-5 leaf stage due to lack of suitable time for adequate recovery and development of vegetative bolls needed to compensate for losses, more so than that of the 2-3 leaf stage. This experiment did not investigate the effects of deer feeding when seedlings are killed and stand loss results, and this experiment also quantified yield losses when all plants (the entire planted area) were affected. Therefore, yield loss assessments and/or replanting decisions in growers fields should be calculated on affected areas alone. Seedcotton yield losses ranged from 20 to 30 percent of the affected area when feeding occurred at the 2-3 leaf stage. Averaged across environments in which a significant loss occurred, yield losses were 26 percent in the affected area when deer feeding occurred at the 2-3 leaf stage. Seedcotton yield losses ranged from 18 to 36 percent of the affected area when feeding occurred at the 4-5 leaf stage. Averaged across environments, yield losses were 29 percent in the affected area when deer feeding occurred at the 4-5 leaf stage. Although yield losses were generally less when feeding occurred at the 2-3 leaf stage, this stage appeared to be more sensitive to seedling death as there is a greater risk that feeding could occur below the cotyledons. Although yield losses were generally greater when feeding occurred at the 4-5 leaf stage, this stage appeared to be more resilient to seedling death as seedling were more robust and feeding occurred consistently above the cotyledons.

Stand loss and Replanting Decisions:

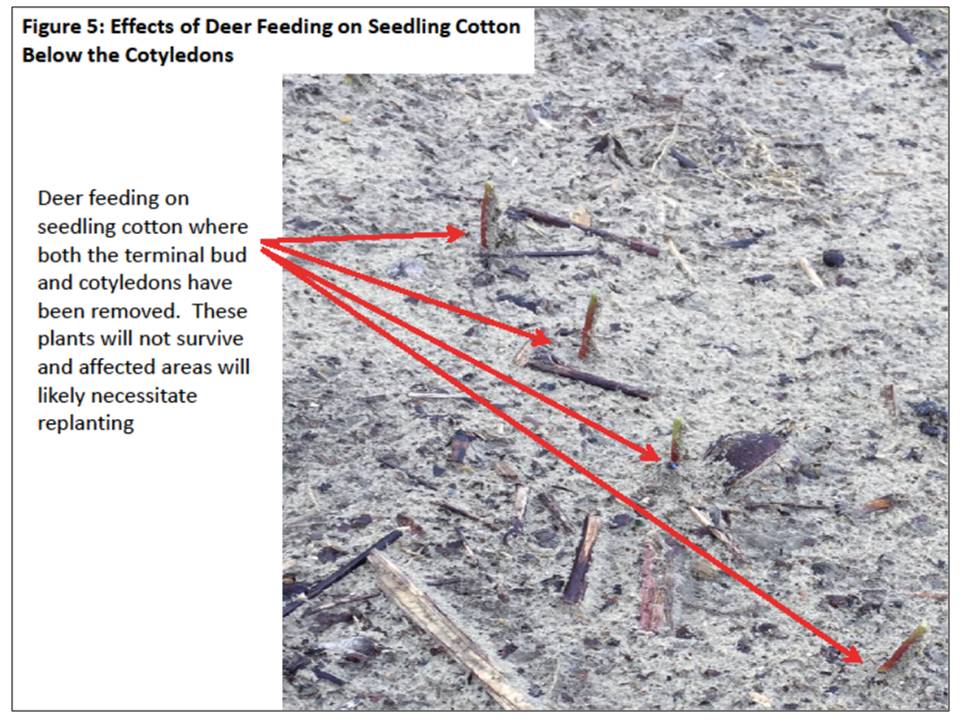

In many common cases, deer feeding occurs on young cotton (cotyledon cotton to 2-leaf cotton) where seedlings are damaged below the cotyledons (Figure 5). In these cases, the terminal bud and all of growth-supporting plant tissue needed for new vegetative branches is lost, and these plants will soon die. If a significant area of a field is affected in this manner, replanting may be justified.

Replanting decisions should be made similarly to that of hail damage or poor emergence situations. If deer feeding has occurred below the cotyledons, consider that as a dead and lost seedling. In many cases, feeding in this manner more commonly occurs during the early part of the planting window when little to no other preferred food sources are available. Generally, the likelihood of this degree of damage decreases towards the end of the planting window, however there seems to be exceptions every year, primarily in areas where fields are smaller and there are high numbers of deer and where cotton is planted in a close proximity to bedding areas. Thorough scouting of fields should occur soon after emergence and throughout the planting window. In other words, growers shouldn’t wait until the planting season is over before evaluating fields so that action (replanting) can be taken while there is still time. Ideally, feeding that kills cotton to this degree occurs primarily on the edges of fields so that these areas can be treated and managed differently than the rest of the field. However there have been cases where the entire field may be affected to this degree. A good general rule of thumb is that replanting can be justified when 50 percent of the planted area is occupied by three-foot skips or greater. Growers must then evaluate surviving plants and document planting date and growth stage when feeding occurred. Any potential yield loss of surviving plants must also be considered when making replanting and management decisions. Lastly growers should consider soil moisture status and if it is sufficient for replanting, the time remaining in the planting season for replanting to occur, and the likelihood that damage will or will not occur again on replanted cotton.

Management of Surviving Cotton and Replanted Cotton:

Ideally, areas of fields affected by deer feeding will be isolated to field edges or particular areas within the field, although this is commonly not the case. When cotton damaged by deer feeding is isolated to specific areas or edges, it is best to treat those parts of the fields differently from the unaffected areas. Treat replanted areas similarly to very late planted fields. In replanted areas, it is very important to manage for earliness or maximizing retention of the earliest-set bolls in these areas. Replanted areas may be more heavily impacted from losses due to insects, therefore thorough scouting and very timely insecticide application is necessary to retain early-set bolls. Replanted cotton may be more sensitive to fruit loss from drought in which timely irrigation could help. Lastly, using a different PGR management strategy can help retain more earlier-set bolls in replanted areas. Growers may need to delay defoliation as long as possible (a few days before first frost) in these areas to fully mature the entire boll population which may require harvesting these areas at a later time.

For areas where plants survived but received damage from deer feeding, it is safe to assume that some yield loss has likely occurred and that maturity is delayed. When growers hear that maturity is delayed, their first instinct is to apply PGRs aggressively to promote earliness. While this may be appropriate for replanted cotton in high-moisture soils, this may not be appropriate for deer damaged cotton. Although maturity has been delayed in surviving plants, it is important to understand that development is now behind schedule and extra time will now be required to first initiate new vegetative branches, and secondly, to develop bolls on those vegetative branches. Therefore, growers should actually be taking action to encourage or stimulate growth for a good while after damage occurs until we approach our last effective bloom date (typically August 20-31st depending on the year and location within the state). There are no miracle or remedy products that have been researched for this purpose, and the best outcome will likely result from proper fertilization, adequate soil moisture, and good heat unit accumulation. As yield potential is likely lower in deer damaged cotton, additional fertilization beyond soil test recommendations will not likely result in higher yields. Timely insect control and irrigation also important in these situations as well, which should be shifted to reward a later-developing boll population to retain and develop all bolls made before the last effective bloom date. Furthermore, it is more important for growers to avoid practices that may further delay maturity or discourage growth throughout most of the summer months. This may include any practice that may cause injury or stunting to the crop (herbicides, foliar fertilizers) and aggressive PGRs early in the season. During early/mid August, as the last effective bloom date approaches, PGRs could be applied in a manner to minimize additional growth beyond the last effective bloom date. Growers may need to delay defoliation as long as possible (a few days before first frost) in these areas as well to fully mature the entire boll population which may require harvesting these areas at a later time.

For fields where stand loss was not significant enough to justify replanting, and there is a mix of deer damaged plants and normal plants, it is best to manage according to the majority of plants in that field, especially according to the higher yielding areas of that field. This is a common scenario and is often complicated in terms of management decisions. It is generally recommended to delay the first PGR application until first bloom or mid bloom, depending on planting date, to allow deer damaged plants to somewhat develop their new vegetative branches. However, growers should not wait indefinitely where normal plants may be penalized from rank growth. This is a difficult decision and is weather dependent in dryland environments. Generally speaking, it is best to slightly delay the first PGR application (if nearly half of the field contains deer damaged plants), use an overall moderate PGR strategy while preventing rank and unnecessary growth (more appropriate for early planted cotton), and slightly delay defoliation to provide more time for developing vegetative bolls on deer damaged plants. Timely irrigation and insect management can also reward fields that fall into this scenario as well.